No War, No Invasion, No Dice: The Alien Enemies Act Isn’t a Blank Check

When your deportation strategy relies on the law that justified internment camps, it’s probably not the constitutional flex you think it is.

By Kyle K. Courtney | Mostly Lawful

What do you get when you mix a 227-year-old law, a modern deportation plan, and gang tattoos? A Constitutional dumpster fire.

Since the moment Donald Trump took office, his administration has treated immigration law like a choose-your-own-adventure novel — except every page ends in detention.

So, it should surprise no one that the latest chapter in this saga involves dusting off the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, a statute written when the U.S. was barely a country and worried about being invaded by… the French.

Multiple district courts in New York, Texas, and Colorado have issued restraining orders against the use of the Aliens Enemies Act (AEA). The newest case, with the strongest language to date, was from the United States District Court for the Western District of Texas. There a federal district judge struck down the Trump Administration’s use of the Alien Enemies Act to mass-deport Venezuelan nationals allegedly affiliated with the Tren de Aragua gang.

Judge Fernando Rodriguez Jr., ruling from the Southern District of Texas, issued the most expansive decision yet in a growing number of challenges to the White House’s attempt to use this rarely invoked 1798 statute. In a thorough 36-page opinion, Judge Rodriguez — himself a Trump appointee — offered not only a legal rebuke but a sort-of philosophical rejection of the White House’s efforts to transpose an 18th-century wartime law into 21st-century immigration enforcement.

The Alien Enemies Act of 1798 is, incredibly, still on the books — a legal antique passed back when powdered wigs were trending and duels were a legitimate conflict resolution strategy. This statute gives the U.S. president sweeping authority to detain, restrict, or deport foreign nationals from enemy nations — during times of declared war or actual invasion. And by sweeping, we mean "apprehended, restrained, secured, and removed" — pretty much the whole constitutional rights piñata, shattered in one swing.

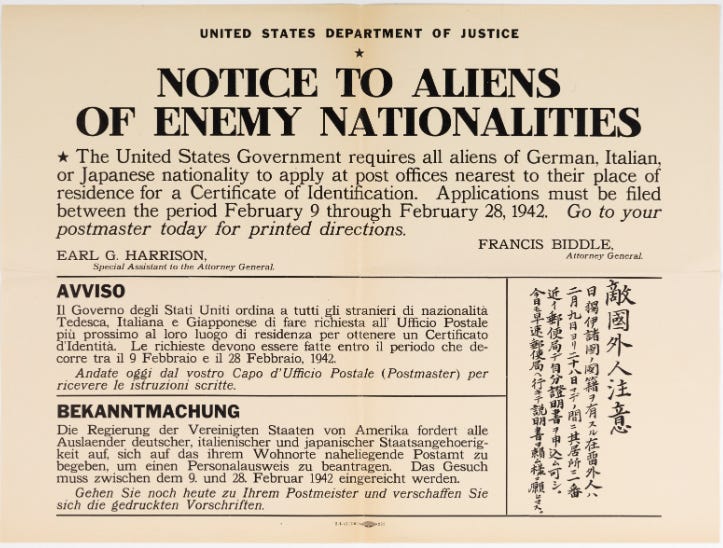

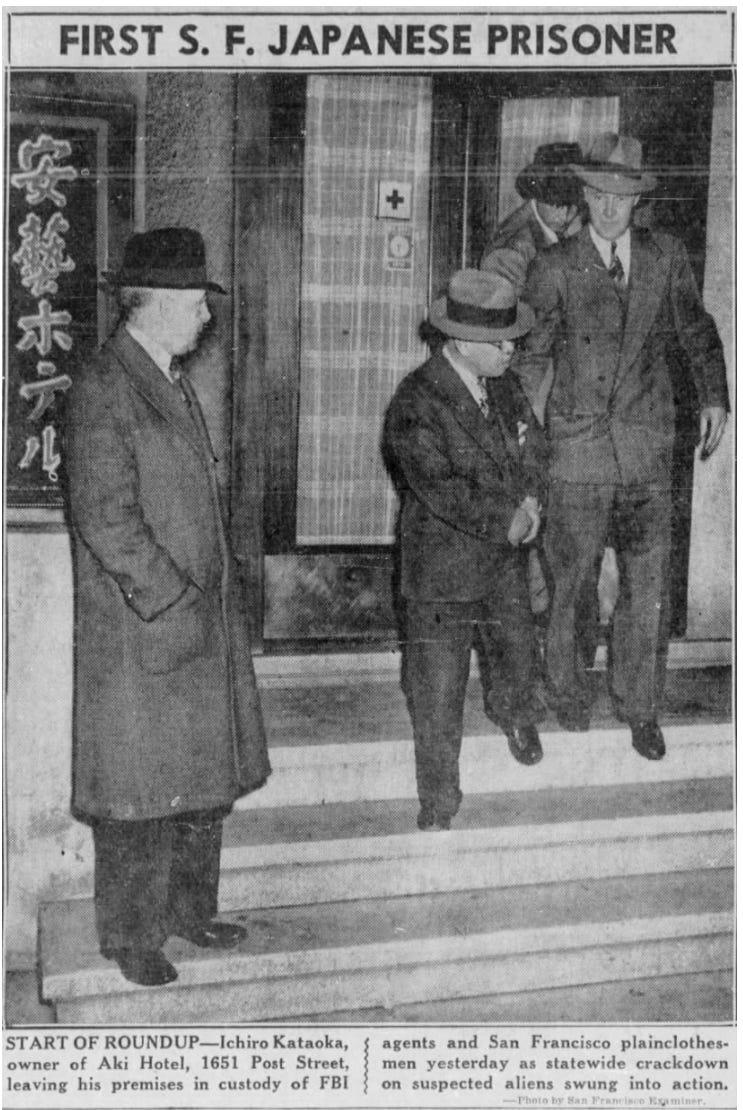

Historically, this statute only made appearances during declared wars like 1812, WWI, and WWII. But even in those times, the consequences were severe. Think: the legal groundwork for the mass internment of Japanese Americans. (Yes, that one – more on that below).

Fast-forward to today, and the Act has staged a comeback — not in a historical re-enactment society, but in actual immigration policy under former President Donald Trump, who has tried to reframe immigration through the lens of wartime emergency.

This week’s Mostly Lawful dives into the Act’s origins, its appalling use during WWII, the infamous Korematsu ruling, and then walks briskly to the present, where we explore how a 227-year-old law was dusted off, reinterpreted, and arguably misused to sidestep immigration due process.

And in the end, we learn that the “invasion” may have been more rhetorical than real.

What’s Required to Use the Alien Enemies Act?

Contrary to recent rhetoric, the Alien Enemies Act has strict legal conditions. You can't just slap the word "invasion" on a press release and expect to bypass the Constitution.

The AEA contains two provisions: a conditional clause and an operative clause.

The conditional clause limits the AEA's substantive authority to conflicts between the United States and a foreign power. Specifically, there must be (i) “a declared war between the United States and any foreign nation or government, or” (ii) an “invasion or predatory incursion perpetrated, attempted, or threatened against the territory of the United States by any foreign nation or government,” and (iii) a presidential “public proclamation of the event.” If these conditions are met:

[A]ll natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects of the hostile nation or government, being of the age of fourteen years and upward, who shall be within the United States and not actually naturalized, shall be liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured, and removed as alien enemies. The President is authorized ... to direct ... the manner and degree of the restraint to which they shall be subject ... and to provide for the removal of those who, not being permitted to reside within the United States, refuse or neglect to depart therefrom; and to establish any other regulations which are found necessary in the premises and for the public safety. 50 U.S.C. § 21.

If the pre-conditions are met, the AEA does vest the President a near-blanket authority to detain and deport. Yet, the central limit to this power is the Act's conditional clause—that the United States be at war or under invasion or predatory incursion.

So, the Act is triggered only during a time of declared war by the United States against a foreign nation. This means an official war declaration by Congress — something that hasn’t happened since World War II. Courts have generally required a formal legal state of war, not just hostile relations or policy disputes.

Alternatively, the Act can be used if a foreign government is actively invading or attempting to invade U.S. territory — or committing a "predatory incursion" (an archaic phrase that roughly translates to a violent cross-border attack by a foreign power).

However, this does NOT include criminal activity by non-state actors, asylum seekers at the southern border, or domestic gang violence not directed by a foreign state.

The statutory language and judicial precedent are clear: the Act applies only to enemy nations or their agents. That’s why the Trump Administration’s attempt to stretch the definition to cover transnational gangs — even violent ones — hits a legal wall. Unless Tren de Aragua is the Venezuelan National Guard in disguise (spoiler: it’s not), the statute does not apply.

Legal and scholarly consensus, reflected in recent court rulings, maintains that this law is not a blank check for wartime-style immigration enforcement in peacetime.

Legal Foundation, History, and Limits of the Alien Enemies Act

During the War of 1812, President James Madison issued a proclamation requiring subjects of Great Britain and Ireland “to report themselves to the marshal of the state in which such aliens resided.” (and this was reviewed in a case called Lockington v. Smith, 15 F. Cas. 758 (C.C.D. Pa. 1817) discussing the 1812 proclamation.)

More than a century later, in 1917—after the United States had declared war against Germany and entered World War I—President Woodrow Wilson invoked the statute to restrict the rights of German nationals. His orders curtailed their ability to own weapons or travel freely and provided for their possible confinement.

Then, one day after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued a “public proclamation . . . that an invasion has been perpetrated upon the territory of the United States by the Empire of Japan.” 6 Fed. Reg. 6321.

The following day, he further proclaimed “that an invasion or predatory incursion is threatened upon the territory of the United States by Germany.” Later there were simultaneous proclamation regarding Italy and extended the declarations to include aliens from Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria, after Congress declared war on those countries.

In July 1945, after the Axis powers in Europe had unconditionally surrendered, President Harry Truman issued an amended proclamation allowing for the removal of Japanese, German, Italian, Bulgarian, Hungarian, and Romanian aliens deemed by the Attorney General “to be dangerous to the public peace and safety of the United States because they have adhered to the aforesaid enemy governments or to the principles of government thereof.” 10 Fed. Reg. 8947 [Truman]

As the record reflects in this brief history, the AEA was explicitly limited to non-citizens—a point that courts have long emphasized.

Historically, courts have interpreted the statute narrowly. In Ludecke v. Watkins (1948), the Supreme Court upheld the AEA’s application only in the context of an ongoing declared war—even after World War II had formally ended in Europe. Crucially, however, the Court has never upheld its use during peacetime or in the context of undeclared conflicts. The statute presumes a traditional wartime framework involving nation-states, not loosely affiliated criminal networks or migration flows.

Legal scholars and civil liberties advocates argue that applying the AEA to unauthorized immigrants during peacetime stretches both its language and its constitutionality beyond recognition. It effectively allows the executive branch to unilaterally redefine what constitutes an “invasion,” sidestepping Congress’s exclusive power to declare war.

Legal Chaos and the Shadow of Korematsu

But, despite what the news states, these AEA cases aren’t about procedural fights — it’s about historical memory and legal accountability.

At the heart of the controversy lies the disturbing precedent of Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944), where the Supreme Court upheld the mass exclusion and incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII in U.S. government internment camps. Fred Korematsu, a U.S. citizen of Japanese descent, had defied the exclusion order. The Court ruled against him, validating military orders that forced more than 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry — the majority of them U.S. citizens — into internment camps.

The justification then? National security. The evidence? Nonexistent. The true motive? I think we have all seen that some legal decisions in the U.S.’s history was as a toxic cocktail of racism, wartime hysteria, and institutional cowardice before. In the years since, Korematsu has come to symbolize one of the darkest chapters in American constitutional law.

What made this chapter of American history even more tragic was that the government knew Japanese Americans posed no real threat. (Sound familiar?) Intelligence from both the FBI and the Office of Naval Intelligence had already concluded there was minimal risk of sabotage or subversion by a so-called “fifth column.” A White House-commissioned investigation—the Munson Report—submitted just weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor, also found that Japanese Americans did not pose a threat to national security. Nevertheless, the government proceeded to imprison them, not out of military necessity, but as a political expedient to calm public fears that the Imperial Japanese Army might invade—with support from the Japanese American community.

It took decades, but the U.S. government eventually admitted the internment was a grave injustice. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, which issued a formal apology and reparations to surviving Japanese American internees. The Civil Liberties Act acknowledged that the detentions were based on “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”

[And yes — adding historical irony to constitutional injury — one of the most decorated military unit in American history, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, was made up almost entirely of Japanese-American soldiers. Many of them enlisted from inside those very camps created by the AEA. These citizens with Japanese heritage fought bravely in Europe even while their families were imprisoned back home by the country they served. Their motto? “Go For Broke.” They did. And they proved just how wrong the government had been about their loyalty to the U.S.]

And this historical use of the AEA and subsequent apology by the U.S. government has been noted in the present AEA cases. For example, in J.G.G. v. Trump, No. CV 25-766 (JEB), 2025 WL 890401 (D.D.C. Mar. 24, 2025), U.S. District Judge James Boasberg issued temporary restraining orders to halt these deportations, citing due process concerns. Later, on April 7, 2025, the Supreme Court, in a 5-4 decision, vacated these orders. The Court determined that challenges to such deportations must be filed as habeas corpus petitions in the district where the detainees are held—in this case, Texas—rather than in Washington, D.C. Supreme Court

While the majority did not address the constitutionality of using the AEA in this context, they emphasized that detainees must receive notice and an opportunity to challenge their removal. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, concurring with Justice Sonia Sotomayor's dissent, penned her own dissenting opinion, alluding to Korematsu, stating:

“But make no mistake: We are just as wrong now as we have been in the past….”

And yet, here we are. Still testing the limits of what one branch of government can do in the name of national security. Still battling the ghosts of Korematsu, in new forms and with new faces.

Welcome Back, Alien Enemies Act (Now with More “Invasion”)

After WWII and Korematsu, the AEA went back to gathering dust. That is, until the Trump Administration started waving it around like a legal Swiss Army knife. The premise? That unauthorized immigration and transnational gangs at the southern border equaled an invasion.

In early 2025, Trump issued a presidential proclamation invoking the Alien Enemies Act against Venezuelan nationals allegedly associated with the Tren de Aragua gang — a violent group originating in Venezuelan prisons. The administration claimed that this was not just a gang issue, but a foreign government sending enemy operatives into the U.S.

Hence, according to Trump, an invasion. Hence, wartime powers. Hence, detentions and deportations without the usual immigration court process.

The National Intelligence Council Spoils the Plot

Much like the classified Munson Report of the 1940s—which concluded there was no threat of sabotage or invasion from Japanese Americans—the National Intelligence Council has issued a similar assessment in the present day. As reported by The Washington Post and Associated Press, the Council, drawing on input from all 18 U.S. intelligence agencies, found NO evidence that Venezuela is directing an invasion of the United States through the gang known as Tren de Aragua.

According to the Post, the NIC concluded that while the gang operates across borders, it does so for profit, not politics. And the assessment confirmed that there is no evidence that President Maduro or his government is deploying them like a criminal Red Army to storm Texas (or anywhere else in the U.S.). In fact, 17 out of 18 intelligence agencies agreed — only the FBI withheld full concurrence.

This finding is a legal problem for the President’s fake wartime agenda. Because the Alien Enemies Act only applies when there is a war or invasion by a foreign government. If the gang isn’t being deployed by Venezuela, then the statutory basis collapses faster than a fake mustache in a wind tunnel.

The president may not simply “manufacture” the required state of war by unilateral proclamation in order to grab these powers under the AEA. The intelligence community’s own conclusions completely contradict the government’s asserted factual basis for invoking wartime authority.

You Call That an Invasion? A Texas Judge Doesn’t Think So

Now that we’ve covered the history, powers, and limitations of the AEA, let’s revisit the recent Texas case.

In court, the Trump administration’s lawyers attempted to present their case in the best possible light, despite its legal weaknesses. Their argument was that the Alien Enemies Act could apply even without a declaration of war or a government-directed invasion, as long as there was some form of “foreign-originated threat”— which is, of course, not what the statute says.

The government contended that Tren de Aragua functioned as a de facto foreign army and that its presence in the U.S. amounted to a “predatory incursion,” - even though the National Intelligence Council had already determined Venezuela wasn’t directing the group. When asked why the government was calling this an invasion when no shots had been fired, no troops had crossed borders, and the alleged “enemy” was just a bunch of tattooed criminals sneaking in through asylum systems, the response was a word salad dressed in national security vinaigrette.

At one point, government lawyers argued that Congress's power to declare war was inconsequential because the president possesses “inherent authority” to act under “invasion-like conditions.” I want to assure readers: That’s not a thing. Not even close. It's akin to enforcing the fire code because someone lit a scented candle.

The government also tried to shoehorn in Ludecke v. Watkins — a case from the end of WWII — as a kind of catch-all precedent. But in Ludecke, the U.S. had actually declared war. The court was not impressed by this revisionist fan fiction.

Judge Rodriguez’s response? A polite but firm legal smackdown:

The President cannot summarily declare that a foreign nation or government has threatened or perpetrated an invasion or predatory incursion of the United States, followed by the identification of the alien enemies subject to detention or removal…..Allowing the President to unilaterally define the conditions when he may invoke the AEA, and then summarily declare that those conditions exist, would remove all limitations to the Executive Branch’s authority under the AEA, and would strip the courts of their traditional role of interpreting Congressional statutes to determine whether a government official has exceeded the statute’s scope. The law does not support such a position. J.A.V. v. Trump, No. 1:25-CV-072, 2025 WL 1257450, at *11 (S.D. Tex. May 1, 2025).

Translation: You can’t call it an invasion just because it makes a mess.

Early in his ruling, Judge Rodriguez rejected the government’s argument that the courts had no authority to even question the president’s invocation of the statute, writing:

“The court retains the authority to construe the AEA’s terms and determine whether the announced basis for the proclamation properly invokes the statute.”

Translation: “Yes, we can read laws. No, you’re not above them.”

While acknowledging that the AEA grants “broad powers,” Judge Rodriguez clarified that those powers are not unlimited — and that judges do have a role in determining whether those powers are being used within legal bounds. He noted that although he had to take the president’s statements at face value — including the contested assertion that Tren de Aragua is controlled by the Venezuelan government — he could still assess whether those statements matched the legal definitions embedded in the statute.

Spoiler: they didn’t.

Judge Rodriguez found that Mr. Trump’s use of the law did not comport with the definitions of “invasion” or “predatory incursion” under the Act. He also emphasized that the historical uses of the Alien Enemies Act — during the War of 1812 and the two World Wars — involved clear conflicts with recognized enemy governments. The present case, he wrote, involved criminal activity by non-state actors, which does not meet the threshold for invoking emergency wartime deportation powers.

This ruling underscores the urgent need to reckon with a law passed in the 18th century that has been periodically used to violate civil liberties in the 20th — and now, in the 21st — all under the pretext of wartime necessity.

Final Thoughts: When a 1798 Law Meets 2025 Politics

The Trump Administration’s flirtation with – and actual use of – the Alien Enemies Act signals a dramatic reinterpretation of this old law. Historically, the Act was tied to clear-cut wartime scenarios. The Trump-era approach hinges on the President’s unilateral declaration of a de facto “war” on loosely-defined threats like gangs or broad classes of immigrants.

It suggests that a president could designate any ongoing problem as an “invasion” by a foreign entity and thereby invoke emergency powers. If accepted by courts, it would hand the executive branch the ability to suspend normal immigration laws and constitutional protections at will, based on an assertion of threat rather than an act of Congress.

Civil liberties advocates argue that this move is an abuse of the Act — a “power grab” that conflates public safety with national warfare. Immigration enforcement cannot proceed under a framework built for global war. The AEA, once dormant, has become a litmus test for the modern presidency’s reach. Whether it remains a relic or becomes a precedent-setting weapon depends on how the courts — and the public — respond.

And if you’re looking for a silver lining? Here it is: the courts still work. Even in an age of executive overreach, legal shortcuts, and press-conference proclamations masquerading as policy, a federal judge can still crack open a 227-year-old statute, squint at it, and say, “Yeah… no.”

That’s not just a legal win — it’s a reminder that constitutional guardrails matter. And that sometimes, the best way to fight bad law is with a really good footnote.