Trump’s Attempt to End Birthright Citizenship: History, Law, and a Reckless Agenda (Part I)

Unconstitutional, Un-American, and Unbelievably on Brand

[Disclaimer: I’m a lawyer. I work at Harvard. I’ve taught countless students who were born in the U.S. under the protections of the Fourteenth Amendment, a constitutional guarantee that should never be up for debate. But this post is my own work, written in my personal capacity. Nothing here is legal advice. If you’re facing a citizenship issue, talk to an immigration attorney—not a Substack. And if you think gutting the Fourteenth Amendment is brilliant policy, I regret to inform you that Stephen Miller already pitched it from his vampire cave, surrounded by printouts of phrenology charts he still considers an underappreciated scientific discipline.]

Citizens by Birth, Targets by Politics

You may have seen birthright citizenship in the news again, because the Trump administration, never one to let precedent, the Constitution, or basic decency get in the way, is once more trying to kill it. This time, it's through an executive order so blatantly unconstitutional that even federal judges appointed by Reagan are calling it “mind-boggling.” But this isn’t just a legal stunt: it’s part of a long, racist tradition of trying to strip citizenship from people born on U.S. soil, particularly the children of immigrants. Let’s talk about where this all comes from, why it’s illegal, and why Stephen Miller’s ghost-white extra-long Nosferatu fingerprints are all over it.

Birthright citizenship has been a constitutional guarantee since Reconstruction, but that hasn’t stopped politicians, pundits, and presidents from trying to gut it. In Part I of our Mostly Lawful post, we trace the deep history of the citizenship debate, the legal battles that shaped it, and the long, mostly failed campaign to roll it back.

Yet, I’ll note to start that in the words of the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black:

“The very nature of our free government makes it completely incongruous to have a rule of law under which a group of citizens temporarily in office can deprive another group of citizens of their citizenship…..[the law] was designed to, and does, protect every citizen of this Nation against a … forcible destruction of his citizenship, whatever his creed, color, or race.” - Afroyim v. Rusk, 387 U.S. 253 (1967)

Historical Background: Slavery, Reconstruction, and the 14th Amendment

The principle of birthright citizenship in America is often discussed through the lens of the Civil War and Reconstruction, and for good reason: these events effectively led to its creation. But its roots, exclusions, and eventual codification trace a longer, more complicated path through early U.S. law.

The Naturalization Act of 1790 was the first law to codify who could become a U.S. citizen, and as you’d imagine, it explicitly limited naturalization to “free white persons,” excluding enslaved people, indentured servants, most women, and implicitly anyone who wasn’t white. Notably, the 1790 Act was silent on the citizenship status of non-white individuals born on U.S. soil, creating a legal gray area that would soon be weaponized.

That ambiguity culminated in the infamous Dred Scott v. Sandford decision of 1857. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Roger Taney held that Black Americans, whether enslaved or free, could never be U.S. citizens. He leaned on the 1790 Act to justify his conclusion and claimed that Congress lacked the authority to confer citizenship on Black people, even those born in the United States.

But Taney’s view did not go unchallenged. Attorney General Edward Bates advised that the Constitution presumes citizenship by birth: “Every person born in the country is, at the moment of birth, prima facie a citizen.” That view was soon codified into federal law.

Before 1866, U.S. law followed the common law tradition of jus soli birthright citizenship. In response to the slavery, Dred Scott, and the Attorney General’s letter, Congress took the next step: it enshrined this principle in the Constitution. The Fourteenth Amendment, proposed in June 1866 and ratified in 1868, states

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States…” (U.S. Const. amend. XIV, §1).

This was, of course, a direct repudiation of Dred Scott and an unambiguous guarantee that no class of Americans, especially newly freed slaves and their children, could ever again be denied citizenship. As one historical account notes, after the Civil War many (including President Andrew Johnson) still hoped to deny citizenship to former slaves, but the 14th Amendment guaranteed that “no class of individuals would ever have to show they were ‘up to snuff’ to deserve citizenship”.

Importantly, the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” was understood at the time to exclude only narrow exceptions, such as children of foreign diplomats or occupying armies, not U.S.-born children of immigrants, regardless of their parents’ status. This interpretation was both the common understanding at the time and later affirmed by the Supreme Court.

In short, the history of birthright citizenship reveals that it was born as a direct response to slavery and white supremacist law. It was not a loophole or policy preference, it was a foundational principle meant to ensure that all persons born on U.S. soil could not be denied legal personhood, equal protection, or belonging. It is, by design, a promise that no government can arbitrarily revoke the birthright of its people.

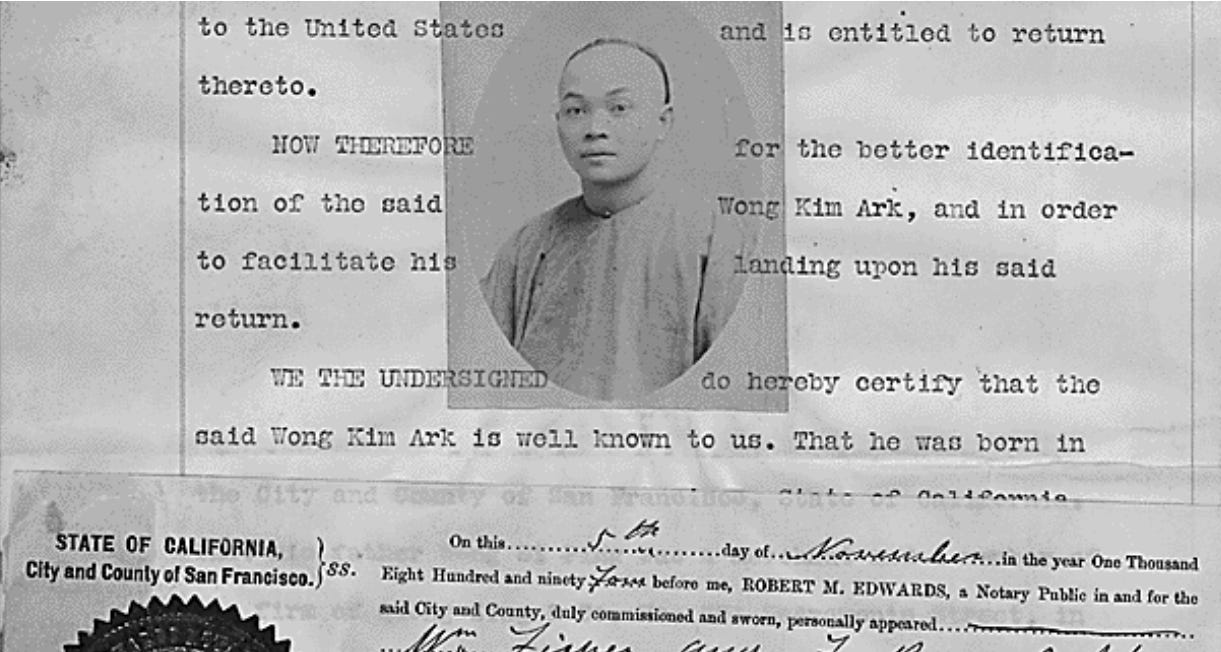

A Century of Court Precedent: Wong Kim Ark and the Supreme Court’s Stance

For over 125 years, the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the 14th Amendment’s Citizenship Clause has remained consistent and unchallenged. The leading case is this space is United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898), which arose when a man born in San Francisco to Chinese immigrant parents was denied re-entry to the U.S. on the theory that he was not a citizen.

The Supreme Court unequivocally rejected that theory. In a 6–2 decision, the Court held that Mr. Wong was a U.S. citizen by birth, because the 14th Amendment “affirms the ancient and fundamental rule of citizenship by birth within the territory… including all children here born of resident aliens.”

Justice Horace Gray’s majority opinion traced this principle to English common law and said the only exceptions were children of foreign diplomats, enemy occupiers, or (at that time) members of Native American tribes not taxed. Critically, the Court emphasized that while the “main purpose” of the 14th Amendment was to ensure citizenship for freed slaves, its text “applies more broadly and is not restricted by color or race,” covering anyone born on U.S. soil and subject to U.S. law.

That 1898 decision has stood for well over a century as settled law. As two legal commentators put it, “the vast majority of the legal academy agrees that the language of the Fourteenth Amendment ensures birthright citizenship,” a principle definitively affirmed by the Supreme Court in Wong Kim Ark. In fact, no court has ever accepted the argument that U.S.-born children of unauthorized immigrants are excluded.

In 1982, the Supreme Court in Plyler v. Doe (interpreting the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause) confirmed that even undocumented immigrants are “within the jurisdiction” of a state, underscoring that unlawful status does not place one outside the law’s protection.

And just this year, U.S. District Judge John Coughenour blocked the Trump policy stressed that “the Supreme Court has resoundingly rejected the president’s interpretation of the Citizenship Clause… No court in the country has ever endorsed [it]. This court will not be the first.”

“I’ve been on the bench for over four decades. I can’t remember another case where the question presented was as clear as this one is,” U.S. District Judge John Coughenour told a Justice Department attorney. “This is a blatantly unconstitutional order.”

In short, birthright citizenship has been part of the constitutional fabric for over 125 years and attempts to undo it fly in the face of unbroken precedent.

A Long Tradition of Failing to Kill the Fourteenth Amendment

Efforts to undermine or abolish birthright citizenship are not new for 2025; they’ve been a recurring feature of anti-immigrant politics for decades.

In the early 1990s, California Governor Pete Wilson backed Proposition 187, a ballot initiative that sought to deny public services, including education, to undocumented immigrants. And it challenged the citizenship of their U.S.-born children. Proposition 187 passed during a period of economic recession in California, when undocumented immigrants were increasingly scapegoated for the state’s fiscal and social challenges (sound familiar?). While this proposition didn’t amend federal citizenship laws, it was part of a broader push to restrict birthright citizenship, and Wilson expressed support for doing so at the federal level.

Though it passed with popular support in 1994, Proposition 187 was ultimately blocked. Judge Mariana Pfaelzer ruled that Proposition 187 unconstitutional in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California.

Around the same time, Senator Harry Reid (D-Nev.) introduced the Immigration Stabilization Act of 1993, which sought to end birthright citizenship for children born to undocumented parents by amending the Immigration and Nationality Act. Years later, Reid called this proposal “the biggest mistake I ever made” in 2006.

During the 1996 Republican National Convention, the party's official platform endorsed ending birthright citizenship: “We support a constitutional amendment to make citizenship for children born in the United States of parents who are not legal residents of the United States contingent upon the citizenship or lawful residency of at least one parent.”

Representative Nathan Deal (R-Ga.) introduced legislation to restrict birthright citizenship repeatedly, beginning in 1993 and continuing for more than 17 consecutive sessions of Congress. He is widely credited with making the repeal effort a regular fixture of Republican immigration legislation.

In 2005, Representative Ron Paul (R-Tex.) proposed multiple amendments to immigration bills designed to end birthright citizenship by denying automatic citizenship to U.S.-born children of noncitizen parents. Paul introduced bills and floor speeches supporting this position across multiple Congresses.

Despite this long trail of political effort, no court, state or federal, has ever accepted the argument that children born on U.S. soil to undocumented immigrants are not citizens. The idea has persisted in right-wing circles, but it has never gained traction in constitutional law.

It remains one of the most settled principles in American constitutional law, but that hasn’t stopped generations of politicians from trying to unravel it.

Stay Tuned: Part II Coming Soon!

(Spoiler: the Fourteenth Amendment still means what it says. But in Part II, we’ll see how well the Trump Administration is doing pretending it doesn’t.)